Fly.io Distributed System Challenge with Go (Part 2)

In my previous post, I covered how I built a basic partition-tolerant broadcast system. While it did manage to perform correctly, it was not exactly performant. There was plenty of room for performance optimizations that could be done - this post covers them.

Efficiency Metrics

Maelstrom, the underlying testbench for the challenge, provided a lot of metrics and charts that could be used to analyze the performance of my algorithm. Here are some of the key metrics:

- Stable latency is a measure of time elapsed for a message to be propagated to all nodes (i.e., visible in the output of

readoperation on every nodes). The latency is displayed in percentiles. For example, astable-latenciesfield with{0 0, 0.5 100, 0.95 200, 0.99 300, 1 400}would indicate a median latency of 100ms, and a maximum of 400ms. - Message per operation is the outcome of dividing the total number of messages exchanged between servers with the number of requests (note that the request count also includes ones that does not require any inter-server communication, such as

read). So if we have the same number of reads and non-read operations, we have to double the number to get the actualmessage-per-opfor broadcasts.

With these criteria under the belt, it was possible to assess the performance of the implementation with better accuracy. The first objective of the performance optimization was to have a message-per-op under 30, and median & maximum latency of 400ms and 600ms, respectively.

Optimization #1: Redefining the Network Topology

Closely reviewing the problem description, I saw that I could ignore the topology message and define my own network! This was significant in many ways.

The more connections, the better?

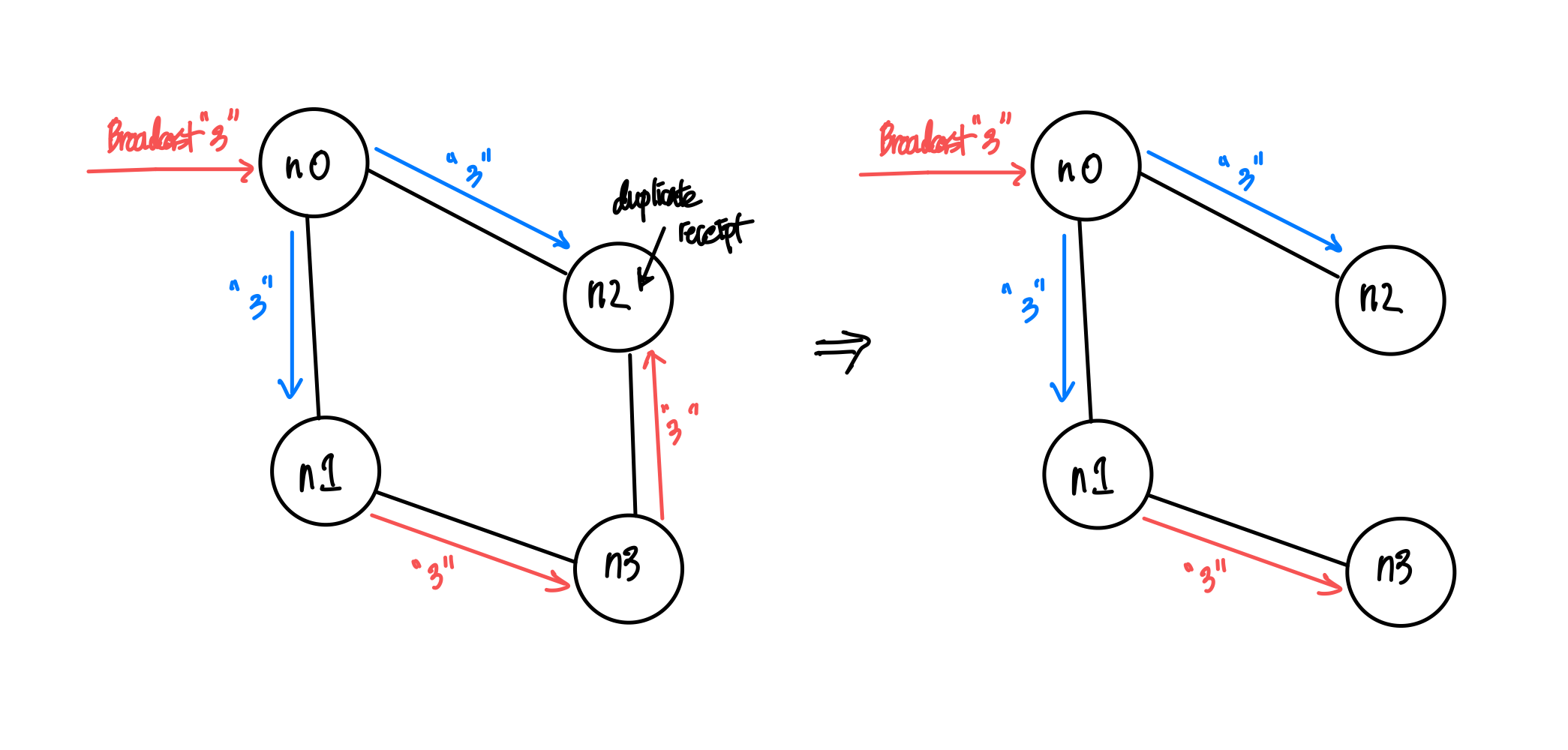

Figure 1: More connections may lead to unnecessary message exchanges

Although the idea of having a fully connected network sounds enthralling, utilizing it in itself may not be the most efficient choice. The biggest culprit, as visible in the left network in the figure above, is the existence of loops. Loops lead to unnecessary sends/receipts of messages, increasing the message-per-op count. A less-connected network in the right, in fact, shows better efficiency in broadcasting a single message. If that’s the case, how could one create a loop-free network?

Trees to the rescue

Well, some might have seen it coming, but spanning trees could do the job here. The loopless property of trees fit perfectly to the situation, and the fact that it spans all nodes makes it a functional network. In fact, it already is being used widely in communication networks, namely the Spanning Tree Protocol (STP).

In the context of this problem, we could simply ignore the topology message and build a spanning tree. Since each node has information about all nodes that constitute the system, it can simply build a tree (and decide which neighbors to be a parent/children) by itself, unlike STP.

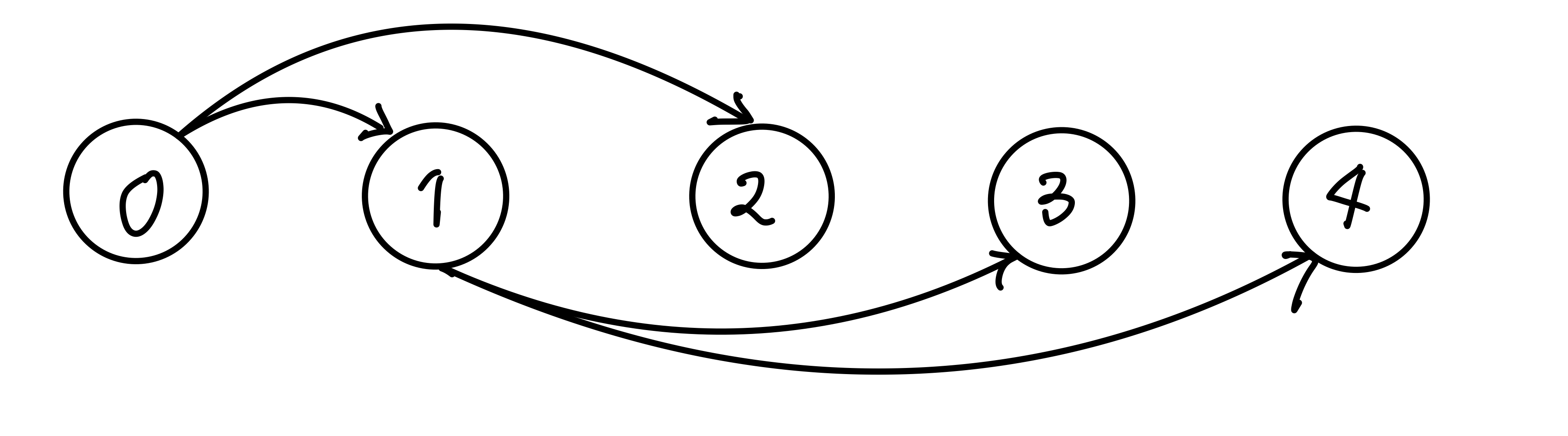

Figure 2: Spanning tree construction with 5 nodes, max 2 children/node

I parameterized the number of children each node can have, and tried tuning these values (num_children). If you crank up this value, the resulting tree will be shallow in depth, which could help the message to propagate faster throughout the network - to an extent.

Contrary to my belief, when I set num_children to be n-1, i.e., the network will be depth 1 with node 0 being the root, and all others connected to it, the median and maximum stable latency actually increased. This may be due to the increased load given to node 0, which would have to handle basically everything by itself. Even when each of the handlers were handled in its own goroutine, it yielded degraded performance.

The optimal num_children for 25 nodes turned out to be between 3 and 5, which would lead to 2-3 level-deep spanning trees, which led to a server msgs-per-op of 22.85, and median and maximum latency of 398 and 403ms. It barely passed the median latency requirement (400ms), but not bad otherwise!

:net {:all {:send-count 48228,

:recv-count 48228,

:msg-count 48228,

:msgs-per-op 24.911158},

:clients {:send-count 3972, :recv-count 3972, :msg-count 3972},

:servers {:send-count 44256,

:recv-count 44256,

:msg-count 44256,

:msgs-per-op 22.859505},

:valid? true},

:stable-latencies {0 73, 0.5 357, 0.95 398, 0.99 401, 1 403},

Optimization #2: Rethinking Inter-Node Communication

For the last section, the bar for efficiency got even higher, with message-per-op less than 20. However, there was a trade-off in latency, as the bar for the median and maximum latency was now one and two seconds, respectively.

Rethinking inter-node communication

Until now, there had to be a message exchange (broadcast request) whenever a node saw a new incoming message. That may help in propagating a message ASAP, resulting in a better stable latency distribution, but it doesn’t help a lot when it comes to efficiency in terms of message counts. How could we save to the extreme, sacrificing some of the latency if needed?

The first idea that came into my mind was message batching. Instead of sending broadcast request on every new message, we could collect new messages until its size equals a predefined BATCH_SIZE constant. Then we could send out the set of new messages collected to the neighbors.

However, relying solely on the batch size as a criterion for sending out messages can be dangerous. If clients send messages just short of BATCH_SIZE and stop sending, there is no way for the node to propagate the messages that it’s holding - breaking the critical liveness requirement.

Psst! Psst!

The main problem from the previous approach was the lack of a temporal demension. Instead of having a upper bound on message counts, we can have a bound on the exchange period. In other words, the nodes will sync with each other periodically, with the set of messages they have at the moment of synchronization.

Alright, will that save us a bunch of messages? Well…not yet. This method of naive sharing will lead to an non-decreasing message size, which will quickly grow impractical as the messages aggregate through time. Instead, the nodes act as if they share gossip. You don’t gossip with someone that already knows the story - you only share with those who haven’t (or at least you think they haven’t) heard of the news.

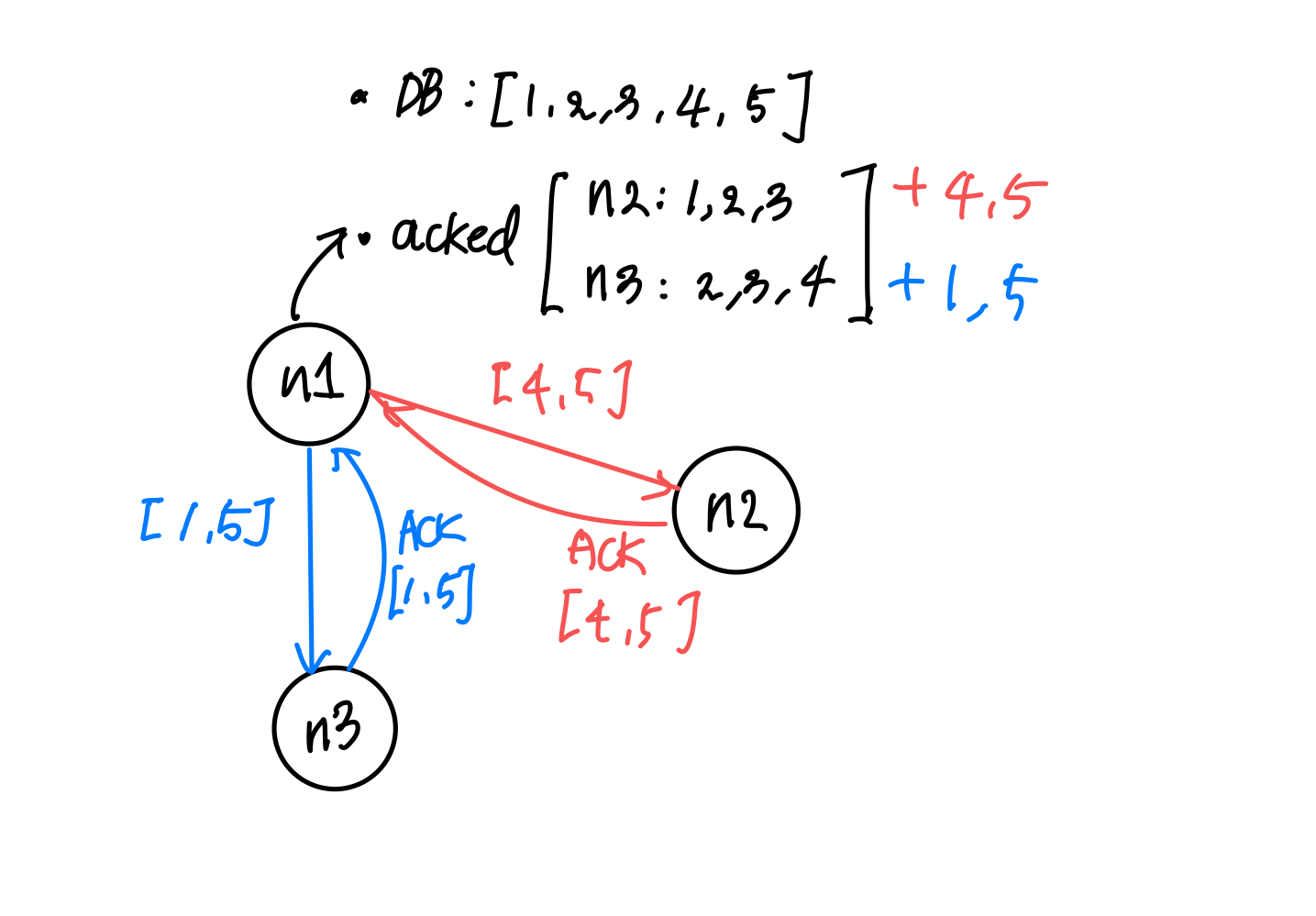

So periodic gossip, a family of the gossip protocol, will be an effective strategy here. In order to make this happen, the nodes would need a separate database of who knows what for each of its neighbor (acked in the snippet below). And then, periodically, each node would gossip to its neighbors a customized set of messages that is presumed to be new to them.

Figure 3: Gossip protocol between three nodes (persp. of n1)

The neighbor that receives the message can then send an ACK of the messages back to the node, which will update its ‘who knows what’ database. Here’s an implementation of what I just said in Go:

// 'Set' of values that this node knows (the `any` is a placeholder)

db utils.MapStruct[int, any]

// keep a record of who knows what (for neighbors)

acked utils.MapStruct[string, map[int]any]

func syncDB(n *maelstrom.Node) error {

// ...

values := *db.Keys() // all values that I know at the moment

body := make(msgBody)

var message []int

var currAcked map[int]any // set of values a neighbor knows

// customize message sending per each neighbor

for _, neighbor := range neighbors {

message = make([]int, 0)

currAcked = make(map[int]any)

// The generic structure of the MapStruct type make it

// impossible to support iteration on a single map value

// without exposing the embedded mutex and map

acked.RLock()

for val := range acked.M[neighbor] {

currAcked[val] = nil //

}

acked.RUnlock()

for _, v := range values {

if _, ok := currAcked[v]; !ok {

message = append(message, v)

}

}

body["message"] = message

if err := n.Send(neighbor, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

}

return nil

}

With syncDB() defined, we could make the node to synchronize messages with its neighbors periodically by adding another event loop as below:

// excerpt from main()

go func() {

for {

if err := syncDB(n); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

time.Sleep(SyncMs * time.Millisecond)

}

}()

Final results

The end result turned out to be much better than I expected: a whopping message-per-op value of 2.98 (compare that to the previous 22.85, which was already optimized from the older version!), and median/maximum stable latency of 1001ms and 1129ms, respectively.

:net {:all {:send-count 9718,

:recv-count 9715,

:msg-count 9718,

:msgs-per-op 5.037843},

:clients {:send-count 3958, :recv-count 3958, :msg-count 3958},

:servers {:send-count 5760,

:recv-count 5757,

:msg-count 5760,

:msgs-per-op 2.9860032},

:valid? true},

:stable-latencies {0 0, 0.5 895, 0.95 1001, 0.99 1099, 1 1129},

So it passes the final hurdle of < 20 messages-per-op, and the median/maximum stable latency requirement with flying colors. Yay!

Next Up: Grow-Only Counter

That concludes the long journey to implementing a performant, partition-tolerant broadcast system. On my next post, I’ll share how I struggled with the subtleties of sequential consistency, and eventually built a distributed, Grow-Only Counter.